A project in progress:

creating the Women's Index (2023) for the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau.

On 30 August, 2023, introduced by Dr Nayahamui Rooney, of ANU School of Culture, History and Language, and co-presenting with Kari James, Exectuive Officer of PAMBU, and Annie Kwai PhD candidate at ANU, an update was given regarding the creation of the Women's Index (2023). Below is the script I used on this day. This project was made possible with funding support from the ANU Gender Institute.

I acknowledge that I am speaking to you from the lands of the Wurundjeri people, of the Kulin nations, a location where sovereignty was never ceded. I pay my respect to their Elders, past and present and know I am a guest as I wander their mountains and waterways. I recognise and respect the numerous First Nations people who are this land's first historians and archivists.

Today I’ll briefly explain how I became involved in this project, how records were selected to be featured in the Index and provide two samples of the information to be included in the Index. To be clear, the 2023 Index is not an analysis of PAMBU as a surrogate archive concerned with issues of provenance and dissemination, but rather, a project that highlights the research potential of the collection, primarily for professionals and academics, and hopefully with enticements for personal and public researchers too. This is a progress update, and now, I am researching and finalising content for the Index while also creating a template of questions and steps that could guide later contributions. I welcome suggestions and questions at the end of today's session or later.

Finding aids are a valuable research tool for often time-poor researchers. These

documents enable institutions to use various methods, keywords, and associated

record suggestions to compel users towards certain collections.

My involvement with PAMBU started when I sought London Missionary Society Pacific

Island records that contained women's voices and actions from the mid-19th and early 20th centuries. Searching for women in LMS records meant I used finding aids from the School of African and Oriental Studies, the National Library of Australia, the State Library of Victoria and the book Manuscripts in the British Isles Relating to Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific. These aids highlighted items like committee reports and letters, showing the boon for Pacific historians that came from missionaries’ bureaucratic tendencies. They were also male-centric in categories and descriptions.

With limited evidence of women in these finding aids, I was ecstatic to locate the work of Gillian Scott’s Women in the Pacific Guide. Scott’s 1992 guide is an important example of presenting a focused perspective on women’s knowledge in a surrogate grounded in men's work and thoughts.

The 2023 guide furthers Scott’s foundational work, assuming a contemporary framing to focus on women whose voices need to be louder in this historical record- Pacific Islanders, big women, wives, junior missionary nurses. The project draws on research methodologies of historians like Diane Langmore, Martha Macintyre, Margaret Jolly and Patricia Grimshaw who analysed original records in archives to locate women’s experiences of domesticity and family in the nineteenth century.[1] British historian Rosemary Seton and imperial historian Robert Bickers suggested in order to move beyond the ‘epic chronicles’ of the early twentieth century, historians need to consistently reexamine records, like those from the PAMBU, to produce new histories focused on previously marginalised individuals and communities.[2] Thereby demonstrating that new presentations of old materials have much value for the next generation of researchers.

Since many of the items in PAMBU were created by European authors, these are sometimes complicated records of encounters between European and Pacific Islanders. As Doug Munro and Brij Lal stated in 2006, the way they saw Pacific histories of the future was that they were to be the consequence of scholars ‘at the various helms, manning the rigging, charting divergent routes, and negotiating the reefs and inlets that were overlooked or discarded by Canberra’.[3] Historian Tiffany Shellam’s analysis of Australian exploration archives and records regarding indigenous intermediaries has revealed that archive records are messy constructs. The moments in which meaning is unclear or the authority of Indigenous intermediaries is acknowledged were ‘downplayed or deleted in later archival mediations’, which Shellam notes make them ‘hard to locate and difficult to decipher’.[4] Assuming a multifaceted, or I prefer the term kaleidoscopic approach, this collection is viewed as a series of historical artefacts, ripe with dynamic potential, as the next generation repurposes records for ‘new histories’.[5] The PAMBU records contain numerous voices and, as the analogy of seafaring indicates, collaborative efforts- complimentary action, shared knowledge, divergent approaches- yield better outcomes than independent actions—something that I will speak more about in a moment.

The initial project aim was to illuminate the collection's value in association with women's records by selecting and highlighting records that broadly demonstrated the significant holdings of the PAMBU collection. We needed to be realistic about how many records could be processed in line with budget and time allowances.

Kari, Nick, Annie and others in the PAMBU office in Canberra located records to include in the index and entered them into a database.

It was quickly determined that quantitative and medical data records were to be excluded from the public-facing Index due to concerns regarding colonial practices of record-keeping and the consideration of potential right to privacy issues.

I framed the research choices using analytical discussions such as those found in Texts and Contexts: Reflections in Pacific Islands Historiography and regarding major PAMBU topical collections.

Other practical considerations involved representing the collections. What periods were covered? What locations were discussed? Was the item a diary, medical records, or a publication? Where was the author located at the time of writing?

Eventually, it was decided that the samples would represent one of five broad categories: missionary, trader, research, royalty and government, and women as intermediaries and translators.

Working remotely on this project from the state of Victoria highlighted the value of multiformat materials in collections like PAMBU. Before 2014, access to the material was provided to researchers via microfilm and print. Thereafter, access has shifted to digital format. I used a combination of digitised records and microfilmed records to research PAMBU. A membership with the National Library of Australia provides access to digitised records via the PAMBU catalogue, whereas a general State Library of Victoria membership allowed me access to numerous microfilmed records.

As I examined and researched my chosen records, discussed findings with Kari and Annie, and reviewed records as they appeared in the Index database, it became apparent the selection could be expanded. Examining the PAMBU records, I chose through the lens of cultural, gender and social history scholarship highlighted absences in the Index; children, blackbirding, women’s collectives, genealogies and ecological knowledge.

Few photographs and cartographic representations in the selected material, and the lack of research time hindered the pursuit of women in photographs, who are often unnamed and unattributed.

Engaging with the records shows me that there should be a greater connection between the records and users involving the communities from where these records were created. My inability to read languages other than English meant I could not read many of the Tongan records and raised questions about whether I should. I perceive the linguistic and cultural diversity of the PAMBU collection to be an advantage for researchers and an opportunity to foster Pacific-Islander-led research opportunities and interdisciplinary collaborations. As a non-Pacific Islander historian, I recommend that future contributions to the Women’s Index be made in association with a Pacific Islander scholarship group.

After locating and examining records, the most urgent question was how I would create a series of topical vignettes to highlight the chosen items in the index, short accounts produced through deep research and analysis. The productive use of vignettes in finding aids was superbly demonstrated in Land of Opportunity: Australia's post-war Reconstruction by Australian political historian Stuart Macintyre and former NLA librarian Graeme Powell for the National Archives of Australia. Since women’s archives and indigenous collections are more likely to have informational absences, this became a block to creating vignettes, so I looked for new ways to present this information.

The output now is evolving to appear more like a brief significance assessment. Questions that occurred while examining records for the Index were: What other archive or library collections did the record link with? What aspect of Pacific history did it speak to? Whose voices were present? Were there restrictions, or should there be, on use or access? What languages are present?

With this framing in place, I’ll provide samples from PAMBU records. I’m excluding the Tongan and Rapa Nui records- records concerned with monarchy, government, and research- as I need more time researching and understanding the cultural significance of these diplomatic and anthropological records.

The first item is a journal by Sarah Taber, a woman identified as a whaler's wife. Microfilmed by PAMBU in 1976 as part of the New England Recording Project, these records are part of a wider collection created by American whalers, traders, sealers, and naval vessels. Coverage is primarily mid to late 19th century but does include a few records from the 18th century. PAMBU drove the copying and preservation of these materials. These records are available from libraries such as the State Libraries of Victoria and New South Wales on microfilm.

The journal provides trace evidence of Sarah’s life from 1851-1855. At the time of writing, Sarah was 35-39 years old. Autobiographical details about her upbringing, education, and early marriage are absent, and I haven’t been able to locate these details elsewhere as yet.

Showing brief insight into Sarah’s life, we see evidence of her roles as a daughter, mother, wife, and the people she encountered. Sarah's intermittent approach to journal-keeping restricts a fuller account of her life. She writes of embarking on Wednesday, 10 September 1851. The reader is quickly informed that Sarah would remain with her husband briefly on ‘his voyage [for] as far as the Sandwich Islands’.[6] Then, in a matter of pages, the date indicates two years have passed. Sarah is aware and honest about her poor record-keeping. At one point, she writes while on Honolulu, Oahu on 27 May, 1853, ‘Dear old journal how long I have neglected you Time has not waited for me I have been long looking for letters from home since last.’ An indication that some written forms of communication had greater value, and worth more of her time, than others.

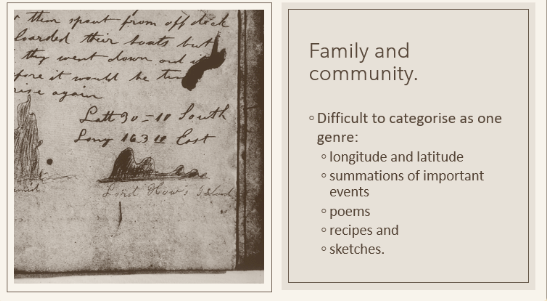

Yet the record has much worth. This is apparent in collectors' difficulty categorising and describing its contents. Sarah recorded longitude and latitude on its pages, hunting grounds, summations of major events, poems, recipes, and sketches of the environment around her.

Sarah’s most substantial entries were about mothering her eldest daughter, Emily. The focus of these entries is medical care and child wellbeing. On Wednesday, March 10 1852 we are informed that ‘little Emily fell down the main hatchway about 3 o'clock while playing about the deck was taken up senseless’. There are six entries, five back-to-back; an unusually continuous account. These daily updates from Sarah detail treatment and home medical knowledge concerning seizures, high fever (122), and loss of sight. This concise record-keeping lasts until Emily recovers.

This journal has another layer of value concerning the presence of local women. These entries occur when Sarah is waiting for her husband to return from hunting whales. In a life guided by the demands of her children’s schooling, church events and waiting for letters from “home” the most detailed mention of local women was a consequence of Sarah writing about an evening walk on Sunday August 7 1853. At this time, an epidemic was travelling through the islands. Walking with ‘Miss Coppin [?] and the children to Mr Mitchels’ Sarah tells us she ‘had a delightful walk’. This description of happiness works in stark contrast to the details written. As during the walk, Sarah writes of seeing ‘an old woman wailing the death of her husband.’[7] A later similar entry provides an outsider's perspective by summating local mortuary rituals. An indication that there were distinctions in women’s lives on the Islands. And evidence of women who didn’t hold the pen themselves.

We see white women working as scribes in Fables of New Britain and New Ireland Collected; a series of creation stories and folklore as told to Ella Collins c1930-1935. The collection has 102 double pages and was digitised from microfilm in relation to this project. The entries in the book are almost a clean copy without errors. This indicates that a draft would have been created in the field and the preserved copy elsewhere. Inscriptions at the start of each story indicate a language group or a village.

Biographical details about Collins are available through the NLA Trove newspapers online. Collins joined the Methodist Mission at Vun-airi-ma, New Britain, in 1925. This was about 32 kilometres from Rabaul. She worked in the region as a teacher until 1932. Collins voice is a strong force in articles that appeared in The Methodist (Sydney, NSW : 1892 - 1954) and Australian Christian Commonwealth newspapers. Providing stories about the ‘great missionary cause’ as experienced by women, in 1928 under the banner of ‘Woman’s World: Topics of Feminine Interest’.[8] . The stories that Collins transcribed could have been utilised by the missionaries as evidence of indigenous populations ‘showing conquest over old customs’.[9] It could also be a record of how relationships- presented by Collins as being inherently violent and punitive- were replaced by Christian, peaceful ways of being.

The records of PAMBU offer an important alternative to the publicly popular, mission-centric news articles produced in the 1920s and 1930s. The stories range from beware of tricksters, competitive men, and evil spirits. The content has some repetition, especially regarding the kinship relationships between men. The stories are not all fables. Some are (see Dog and the Wallaby p57); others are local creation stories about gods, the bringing of the moon and fire (48-49; 59). Some of the stories are gruesome (see The Shell Money House), similar to the original Brothers Grimm tales or contemporary horror stories. Other sections list actions related to marriage, birth, and death traditions of the Baining people, and some are local histories (67;74).

[1] D. Langmore, ‘A Neglected. Force: White Women Missionaries in Papua 1874-1914’, The Journal of Pacific History, 17, (1982), 138–157; H. Choi & M. Jolly, Divine Domesticities: Christian Paradoxes in Asia and the Pacific, (Canberra, ANU Press, 2014); M. Jolly, ‘‘To Save the Girls for a Brighter and Better Lives: Presbyterian Missions and Women in the South of Vanuatu: 1848-1870’, The Journal of Pacific History, 26, (1991), 27–48; M. Jolly and K. Ram, eds., Maternities and Modernities, (Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1998); P. Grimshaw, ‘New England Missionary Wives, Hawaiian Women, and “The Cult of True Womanhood”’, The Hawaiian Journal of History, 19, (1985), 71–100.

[2] R. Bickers & R. Seton eds., ‘Introduction’, Missionary encounters: Sources and Issues, (Cornwell: Curzon Press, 1996), 1.

[3] Lal and Munro, ‘Introduction’, Texts and Contexts: Reflections in Pacific Islands Historiography, University of Hawaii Press, 2006, p3

[4] T. Shellam, Meeting the Waylo, (Crawley, Western Australia, University of Western Australia Press, 2019), 74.

[5] Ibid, 2-3.

[6] 118 AF

[7] 132

[8] WOMAN'S WORLD (1928, March 22). The Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954), p. 19. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article243904497

[9] OUR FOREIGN MISSIONS (1929, September 20). Australian Christian Commonwealth (SA : 1901 - 1940), p. 6. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from